Intro

Welcome! Within this series of blog posts we will go step by step through the process of building your own simple CI system from scratch in Golang. But what exactly are we going to build? We will start small with a simple one-binary-server solution to execute our CI workload. In later posts we will extend and improve it.

At this point one reasonable question can come to your mind: why do we even want to do this? For me, the main reason is: I want to experiment with different technics in CI/CD sphere. And for that I need some basis. In a hope that it will be interesting and useful for others too, I started writing this series.

Here needs also be a disclaimer: It will not be in any shape or form a “Jenkins killer” (at least not from the beginning 🙂). But it should be able at least to build itself from source and provide us an executable. Also I assume, tat you have a basic understanding of what CI is, you have installed and working Go toolchain, and you have a basic knowledge about Go and how it’s module system works.

With introduction out of the way, let’s Go!

Architecture

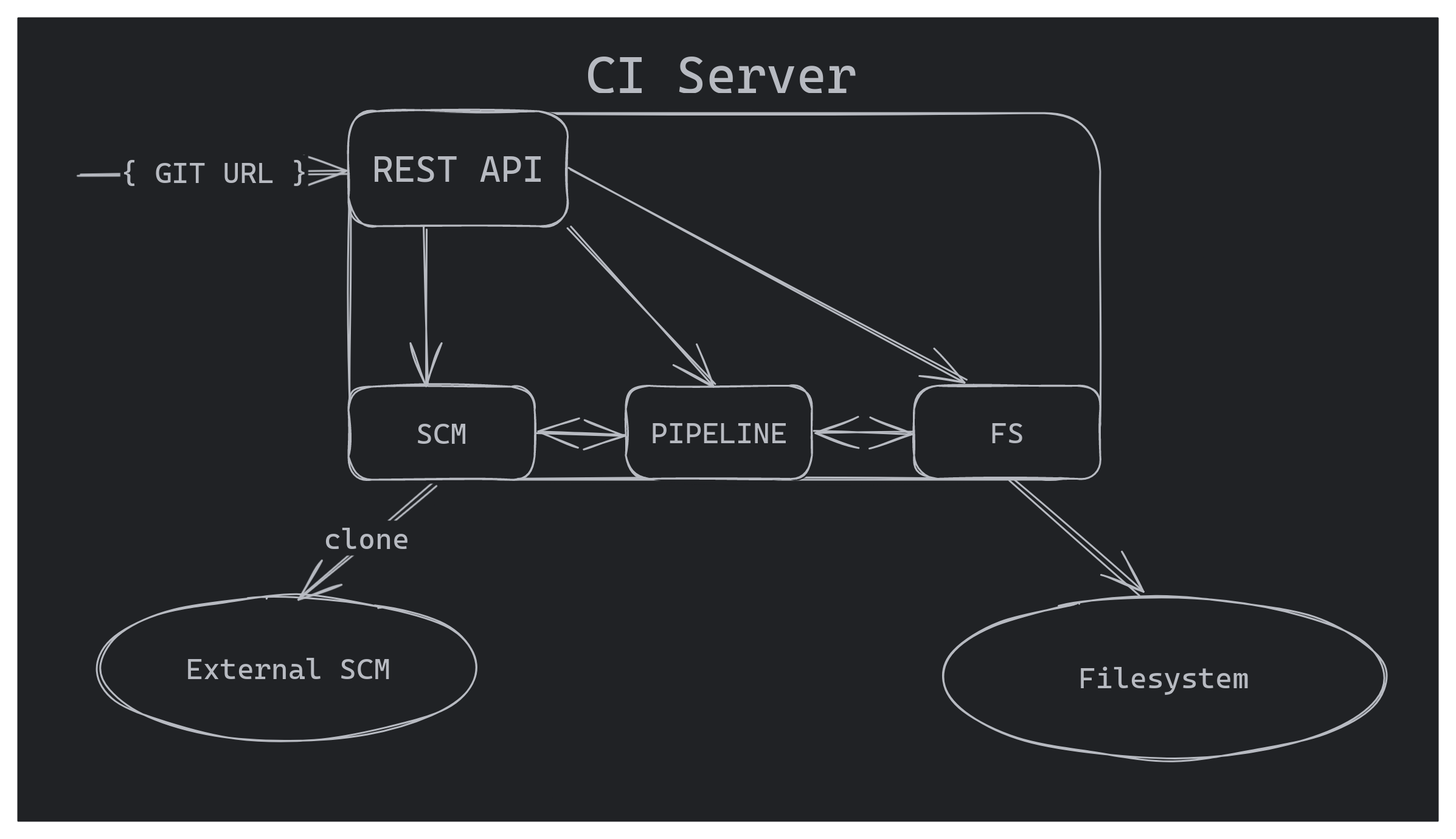

We need to visualize our first destination point. Simple HTTP server, which receives REST API call with the link to remote repository, clones it to temporary directory, finds a file with CI pipeline definition, executes all steps of the pipeline (we will start with testing and compiling) and then copies executable to predefined output directory.

Simplified architecture of our future CI server:

Starting with the server

Let’s start our tour with creation of a new project:

mkdir flow-ci && cd flow-ci

go mod init github.com/flow-ci/flow-ci

You can always found all code in my repo in the branch blog. I tried to do meaningful commits so you can follow the whole process one commit at a time.

Installing fiber framework

For our HTTP server we will be using Fiber framework. You can install it using the command:

go get github.com/gofiber/fiber/v2

New we will need an entry point for our HTTP server. For that we will create file cmd/web/main.go with the following content:

| |

To test that everything is setup as expected let’s run our server:

go run cmd/web/main.go

Now if we navigate our browser to http://127.0.0.1:3000/ we should see the following text:

Hello, World!

To automate/simplify execution of frequent commands let’s create the Makefile:

WEB_APP = web

BUILD_DIR = $(PWD)/bin

.PHONY: test bench run-web

web:

@go build -o $(BUILD_DIR)/$(WEB_APP) cmd/$(WEB_APP)/main.go

run-web: web

@$(BUILD_DIR)/$(WEB_APP)

test:

@go test -v ./...

bench:

@go test -bench=. -benchmem ./...

Now we can compile our HTTP server running the command: make web, and we can start our http server with the command make run-web. Apart from that we can execute all test using make test command, and run all benchmarks using make bench.

Project structure

As we discussed, we will start with very simple implementation, which reacts to a single POST request, with the git repo URL in the payload. Despite that let’s setup basic project structure for it:

/

├┬ cmd

│└┬ web

│ └─ main.go

├┬ internal

│└┬ app

│ └┬ web

│ └┬ handlers

│ └─ pipelines.go

└─ pkg

What do we have here?

cmd- contains entrypoints to our applications, and the code which is only relevant for one specific application. For now it contains only one directoryweb, for the HTTP server.internal- directory with a special meaning, code residing here, can’t be imported from the outside of this repo. Here we will keep our business logic.pkg- here we will put functionality which is not directly related with the business logic of our CI system, and which potentially can be useful in other projects.

Setting up HTTP routing

To nicely structure our HTTP handlers, we will be defining them in separate files inside internal/app/web/handlers directory. All handler`s files will have names reflecting HTTP path where they are exposed (ex. pipelines.go will be exposed as /pipelines/*). Also each file will export function to setup route group (as per Fiber terminology), and this function will follow the naming convention Setup{{Name}}. Here I’m trying to follow a convention defined in this repo from “golang-standards” organization.

So let’s create file internal/app/web/handlers/pipelines.go, where we define our routes group for path /pipelines and all handlers for it.

First we implement our main exported function to setup sub-routes. Here we define our route group for /pipelines/* path and register handler for POST request to /check-it-works sub-route:

func SetupPipelines(app *fiber.App) {

pipelinesGroup := app.Group("/pipelines")

pipelinesGroup.Post("/check-it-works", postCheckItWorks)

}

Then we implement handler itself. For it we need to define a struct which will represent our request body. It contains only one field Url, represented as url in json, xml and form encodings:

type WithRepoUrl struct {

Url string `json:"url" xml:"url" form:"url"`

}

Inside handler we first trying to parse request body, and if this operation succeeds, we respond with the text string "Working with repository:" and the URL we got from the client:

func postCheckItWorks(c *fiber.Ctx) error {

body := &WithRepoUrl{}

if err := c.BodyParser(body); err != nil {

return err

}

return c.SendString(fmt.Sprintf("Working with repository: %s\n", body.Url))

}

Full source of the pipelines.go file:

| |

To finish setting up routing we need to do the following changes to our cmd/web/main.go file:

1package main

2

3import (

4 "github.com/flow-ci/flow-ci/internal/app/web/handlers"

5 "github.com/gofiber/fiber/v2"

6)

7

8func main() {

9 app := fiber.New()

10

11 handlers.SetupPipelines(app)

12

13 app.Listen(":3000")

14}

Here we import our package with handlers and calling a function handlers.SetupPipelines(app) to setup our route group.

Now if we start our server

make run-web

and do a HTTP call with curl:

curl -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/json" \

--data "{\"url\":\"git@github.com:flow-ci/flow-ci.git\"}" \

http://127.0.0.1:3000/pipelines/check-it-works

we should get the following response:

Working with repository: git@github.com:flow-ci/flow-ci.git

Working with git

If you see expected message returned from the server, we can start with more interesting stuff. Let’s add functionality of cloning repository into the temporary folder.

To work with git repositories we will use package go-git, to install it run the following command:

go get github.com/go-git/go-git/v5

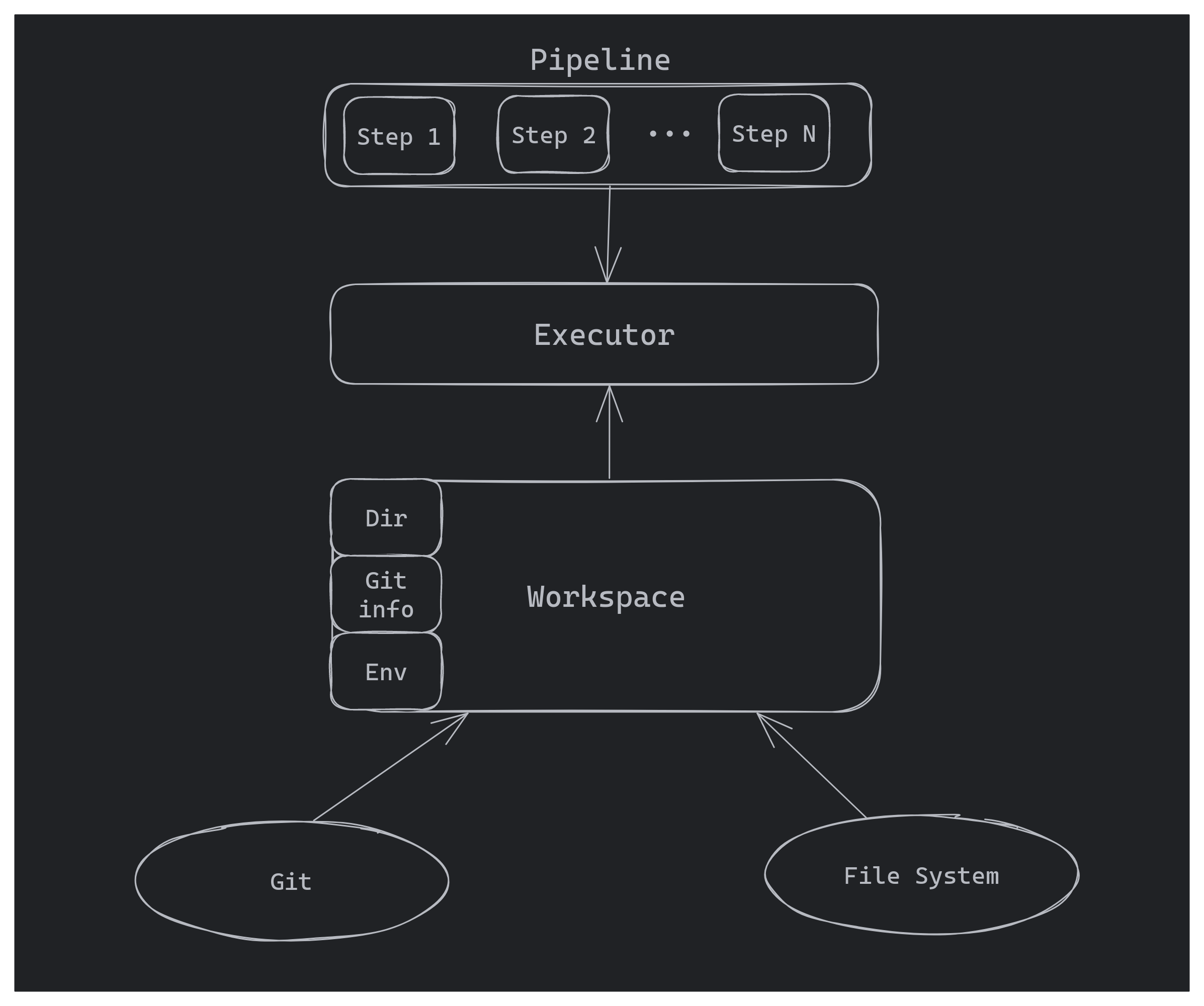

But how should we organize our code? Right now we can split our main CI logic into 3 simple components:

- Pipeline - which will store meta-information (description) of build steps and represent the build process itself;

- Executor - which will contain the code responsible for “understanding” what is stored inside pipeline, and executing it

- Workspace - which will be an abstraction layer for system externals like Git, filesystem, environment, etc…

So the overall process will look like the following: we setup workspace (by cloning Git repo), we instantiate executor for this workspace, and finally we pass a pipeline to executor to run it.

We want our executor code to be testable and we want to scope our dependency on external system components to as close and small code unit as possible, so the good solution for this will be to define Workspace as an interface. Main user of this interface will be Executor, so let’s create a new file executor.go in the directory internal/ci. For each run of CI pipeline we need to know from which branch to checkout the code. We also need to keep track of commit hash, for which we are doing current pipeline run. We will be cloning repo into temporary directory on our server, so we need to keep info about it too. And finally, for some build commands we will need to provide specific environment variables. So our Workspace interface can look something like this:

type Workspace interface {

Branch() string

Commit() string

Dir() string

Env() []string

}

Here we defined methods to get branch name, commit hash, working directory and environment variables. We will expect branch, commit and current working directory as strings, and environment variables we expect to receive as a string slice, each string of which will represent "key=value" pair (for now we will try to store environment in a way compatible with "os/exec" package).

Next we need a struct to hold this data, which will implement our Workspace interface. In file internal/ci/workspace.go we define our struct:

type workspaceImpl struct {

branch string

commit string

dir string

env []string

}

And all the methods to satisfy our interface:

func (ws *workspaceImpl) Branch() string {

return ws.branch

}

func (ws *workspaceImpl) Commit() string {

return ws.commit

}

func (ws *workspaceImpl) Dir() string {

return ws.dir

}

func (ws *workspaceImpl) Env() []string {

return ws.env

}

And finally we need to implement a function to create workspace by cloning Git repository. It will accept three string arguments: root directory, url of remote git repo, and a branch to checkout. And will return either reference to created workspace or an error.

func NewWorkspaceFromGit(root string, url string, branch string) (*workspaceImpl, error) {

First we create temporary directory inside root where all work will happen:

dir, err := os.MkdirTemp(root, "workspace")

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

Then we use go-git package to clone repository into newly created temporary directory:

repo, err := git.PlainClone(dir, false, &git.CloneOptions{

URL: url,

ReferenceName: plumbing.NewBranchReferenceName(branch),

RecurseSubmodules: git.DefaultSubmoduleRecursionDepth,

Depth: 1,

})

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

We set depth of cloning to 1 because we need only the current state of the repository, and we want to conserve disk space.

After cloning repository we are trying to extract information about current HEAD commit, and instantiating Workspace entity with the information we have:

ref, err := repo.Head()

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return &workspaceImpl{

dir: dir,

branch: branch,

commit: ref.Hash().String(),

env: []string{},

}, nil

The whole workspace.go file will look like this:

| |

Now let’s quickly test that everything is working. In general that is not a good idea to put business logic into http handler, but for our case of checking it is fine. Our internal/app/web/handlers/pipelines.go will look like:

1package handlers

2

3import (

4 "fmt"

5

6 "github.com/flow-ci/flow-ci/internal/ci"

7 "github.com/gofiber/fiber/v2"

8)

9

10func SetupPipelines(app *fiber.App) {

11 pipelinesGroup := app.Group("/pipelines")

12

13 pipelinesGroup.Post("/check-it-works", postCheckItWorks)

14}

15

16type WithRepoUrl struct {

17 Url string `json:"url" xml:"url" form:"url"`

18}

19

20func postCheckItWorks(c *fiber.Ctx) error {

21 body := &WithRepoUrl{}

22

23 if err := c.BodyParser(body); err != nil {

24 return err

25 }

26

27 var ws ci.Workspace

28 ws, err := ci.NewWorkspaceFromGit("./tmp", body.Url, "master")

29 if err != nil {

30 return err

31 }

32

33 return c.SendString(fmt.Sprintf("Cloned repository: %s\nFrom branch: %s\nCommit: %s\nInto directory: %s\n", body.Url, ws.Branch(), ws.Commit(), ws.Dir()))

34}

If we execute same curl command from before, we should see the response:

Cloned repository: git@github.com:flow-ci/flow-ci.git

From branch: master

Commit: c1f86ce3ca21408ca612fd045fddcff24bdc0654

Into directory: ./tmp/workspace328313186

Of course, commit hash and the random suffix of temporary directory can/will differ in your case.

Executing first pipeline

We can clone repository, we can get meta information about it (branch, commit, …), but it is not very useful if we do not do anything. Time to define structure and format of our pipelines, and implement execution of shell commands. How about doing this: after cloning the repository our ci will look for file build/flow-ci.yaml, will parse it and start execution of defined in this file pipeline. Let’s start with very simple structure:

name: My First Pipeline

steps:

- name: Download dependencies

commands:

- go mod download

- name: Test

commands:

- make test

- name: Compile

commands:

- make web

So each pipeline will have a name, and a list of steps. Each step in turn also have a name and a list of shell commands to be executed as part of this step.

For parsing yaml we need to install go-yaml package:

go get gopkg.in/yaml.v3

Let’s define Pipeline and Step structs to which our pipeline config file will be unmarshalled (file: internal/ci/pipeline.go):

package ci

type Pipeline struct {

Name string `yaml:"name"`

Steps []Step `yaml:"steps"`

}

type Step struct {

Name string `yaml:"name"`

Commands []string `yaml:"commands"`

}

Next let’s add a function to our workspace implementation to read and parse pipeline file:

func (ws *workspaceImpl) LoadPipeline() (*Pipeline, error) {

data, err := os.ReadFile(filepath.Join(ws.dir, "build", "flow-ci.yaml"))

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

var pipeline Pipeline

err = yaml.Unmarshal(data, &pipeline)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return &pipeline, nil

}

And also extend our Workspace interface:

type Workspace interface {

Branch() string

Commit() string

Dir() string

Env() []string

LoadPipeline() (*Pipeline, error)

}

We are ready to start implementing the core functionality of our ci system: Executor. Executor needs to have Workspace interface as a dependency.

type Executor struct {

ws Workspace

}

type Workspace interface {

Branch() string

Commit() string

Dir() string

Env() []string

LoadPipeline() (*Pipeline, error)

}

func NewExecutor(ws Workspace) *Executor {

return &Executor{

ws: ws,

}

}

Easy and logical so far. On top of that we need a function to run a pipeline:

func (e *Executor) Run(ctx context.Context, pipeline *Pipeline) (string, error)

Here we pass Context as first argument to have more granular control over pipeline execution in future. And one more function to execute pipeline of the repository config:

func (e *Executor) RunDefault(ctx context.Context) (string, error) {

pipeline, err := e.ws.LoadPipeline()

if err != nil {

return "", err

}

return e.Run(ctx, pipeline)

}

Pipeline execution is a straightforward process, we need to iterate over all steps of pipeline, and for each step iterate over it’s list of shell commands:

for _, step := range pipeline.Steps {

for _, cmd := range step.Commands {

// TODO: somehow execute shell command

}

}

But how do we execute shell commands? Luckily for us Go standard library has function CommandContext in “os/exec” package, so we just need to write thin wrapper for it in our workspace implementation:

func (ws *workspaceImpl) ExecuteCommand(ctx context.Context, cmd string, args []string) ([]byte, error) {

command := exec.CommandContext(ctx, cmd, args...)

command.Dir = ws.dir

command.Env = append(command.Environ(), ws.Env()...)

return command.CombinedOutput()

}

Here we pass our current working directory and our environment from workspace and execute shell command, waiting for it to finish, and then returning combined output from the command (stdout and stderr).

Now we can finish implementation of executor.Run function. Let’s also crate string builder, where we will combine our own messages and outputs of all executed commands, so we have a log of a pipeline execution as an output:

func (e *Executor) Run(ctx context.Context, pipeline *Pipeline) (string, error) {

output := strings.Builder{}

output.WriteString("Executing pipeline: ")

output.WriteString(pipeline.Name)

output.WriteRune('\n')

for _, step := range pipeline.Steps {

output.WriteString("Step: ")

output.WriteString(step.Name)

output.WriteRune('\n')

for _, cmd := range step.Commands {

withArgs := strings.Fields(cmd)

cmd = withArgs[:1][0]

args := withArgs[1:]

out, err := e.ws.ExecuteCommand(ctx, cmd, args)

output.Write(out)

output.WriteRune('\n')

if err != nil {

return output.String(), err

}

}

}

return output.String(), nil

}

With all base functionality ready, it is time to write at least one test for our Executor logic, so we can have more steps in our own pipeline. To make writing tests simpler we will use testify package:

go get github.com/stretchr/testify

Let’s create internal/ci/executor_test.go file:

package ci

import (

"context"

"testing"

"github.com/stretchr/testify/assert"

"github.com/stretchr/testify/mock"

)

func TestRunDefaultHappyPath(t *testing.T) {

// Our test goes here

}

Before writing the code of test function we need to prepare mock implementation of Workspace interface, we will not be doing anything super special, everything from documentation example. We just need to create struct which will “implement” our Workspace interface, and with the help of testify package we will have ability to track method calls and assert arguments passed to them:

type mockWorkspace struct {

mock.Mock

}

func (ws *mockWorkspace) Branch() string {

args := ws.Called()

return args.String(0)

}

func (ws *mockWorkspace) Commit() string {

args := ws.Called()

return args.String(0)

}

func (ws *mockWorkspace) Dir() string {

args := ws.Called()

return args.String(0)

}

func (ws *mockWorkspace) Env() []string {

args := ws.Called()

return args.Get(0).([]string)

}

func (ws *mockWorkspace) LoadPipeline() (*Pipeline, error) {

args := ws.Called()

return args.Get(0).(*Pipeline), args.Error(1)

}

func (ws *mockWorkspace) ExecuteCommand(ctx context.Context, cmd string, arguments []string) ([]byte, error) {

args := ws.Called(ctx, cmd, arguments)

return args.Get(0).([]byte), args.Error(1)

}

As for test function, we need to first create instance of our mock workspace:

wsMock := mockWorkspace{}

And then register our expectation, about which methods of workspace we expect to be called, with which parameters, and what they will return:

wsMock.On("LoadPipeline").Return(

&Pipeline{

Name: "Test Pipeline",

Steps: []Step{

{Name: "Step 1", Commands: []string{"cmd1 arg1 arg2"}},

},

},

nil,

)

wsMock.On("ExecuteCommand", context.Background(), "cmd1", []string{"arg1", "arg2"}).Return(

[]byte("Output"),

nil,

)

Then we instantiate our executor, passing our mocked workspace, executing RunDefault method and doing assertions about expected contents of execution log:

executor := NewExecutor(&wsMock)

str, err := executor.RunDefault(context.Background())

assert.Nil(t, err)

expectedOutput := `Executing pipeline: Test Pipeline

Step: Step 1

Output

`

assert.Equal(t, expectedOutput, str, "wrong output")

Now if we run make test command, we should see 1 successful test. With that out of the way, let’s update our /check-it-works handler, to execute default pipeline of provided repository. For that we will need to add support for passing branch name in request body.

Let’s add a Branch field to our WithRepoUrl struct, at this point it makes sense to rename it to RequestBody:

type RequestBody struct {

Url string `json:"url" xml:"url" form:"url"`

Branch string `json:"branch" xml:"branch" form:"branch"`

}

Then we also update the code of workspace creation to pass branch name from the request body:

var ws ci.Workspace

ws, err := ci.NewWorkspaceFromGit("./tmp", body.Url, body.Branch)

if err != nil {

return err

}

And finally we execute default pipeline of repository and return the output of executor (execution log):

executor := ci.NewExecutor(ws)

output, err := executor.RunDefault(c.UserContext())

if err != nil {

return c.Status(500).SendString(output)

}

return c.SendString(

fmt.Sprintf(

"Successfully executed pipeline.\n%s\n\nFrom branch: %s\nCommit: %s\nIn directory: %s\n",

output,

ws.Branch(),

ws.Commit(),

ws.Dir(),

),

)

It is time to test execution of our first pipeline:

curl -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/json" \

--data "{\"url\":\"git@github.com:flow-ci/flow-ci.git\",\"branch\":\"blog\"}" \

http://127.0.0.1:3000/pipelines/check-it-works

In response to this command we should see something similar to:

Successfully executed pipeline.

Executing pipeline: My First Pipeline

Step: Download dependencies

Step: Test

make[1]: Entering directory '/home/vir/projects/go/flow-ci/tmp/workspace2016416224'

go test -v -race ./...

? github.com/flow-ci/flow-ci/cmd/web [no test files]

? github.com/flow-ci/flow-ci/internal/app/web/handlers [no test files]

=== RUN TestRunDefaultHappyPath

--- PASS: TestRunDefaultHappyPath (0.00s)

PASS

ok github.com/flow-ci/flow-ci/internal/ci 1.012s

make[1]: Leaving directory '/home/vir/projects/go/flow-ci/tmp/workspace2016416224'

Step: Compile

make[1]: Entering directory '/home/vir/projects/go/flow-ci/tmp/workspace2016416224'

go build -o /home/vir/projects/go/flow-ci/tmp/workspace2016416224/bin/web cmd/web/main.go

make[1]: Leaving directory '/home/vir/projects/go/flow-ci/tmp/workspace2016416224'

From branch: blog

Commit: 6b8caddc2babd3ecf19e16333f749edc0fae2317

In directory: ./tmp/workspace2016416224

💃 Hooray 🕺! Our first pipeline is executed. Our CI is able to build itself. Serious milestone is achieved, but there is a very long road ahead of us, before this system becomes useful. In terms of functionality we need to add persistent storage, to keep track of all existing projects/pipelines, we need to add minimal web UI. On top of that we also need to think about scalability. Building software is very resource-intensive operation, and one server will not be able to handle the load, so we need to split it into some kind of foreman-worker architecture, where main server is responsible for management tasks, and worker servers are only responsible for executing pipelines. And finally right now, our executor directly executes commands from pipeline, expecting that all required tooling is present in the system. That is not the case in real situations, that is why it makes sense to use containers for execution of pipeline steps.

Outro

This article is already quite big, so I stop here for now. In the next article we will start working on containerization and scalability.

If you encountered any problems please check, that your code is the same as in my repository1.

PS: I would really appreciate any constructive feedback. Please feel free to drop a comment here.

Complete source code for this article can be found in my repository at commit

6b8caddc2babd3ecf19e16333f749edc0fae2317. ↩︎